Crises tend to have similar impacts on markets: fear overtakes greed as the motor of the market, and there is a rapid flight to quality (buy US dollar, US treasuries, Bunds, Gold, etc, etc). Market liquidity seizes up as everyone sells risky assets, hoards liquidity and tightens their risk management standards: these factors reinforce each other and cause a downward liquidity spiral. All these features were present in March 2020, and necessitated massive central bank and regulatory intervention, but an important question is whether or not the market and capital reforms introduced in the wake of the 2007-8 GFC made things better or worse. There are several different strands here, which are often taken in opposition, but which are not necessarily inconsistent with each other:

- The procyclicality of the trading book capital rules constrained banks from making markets

- The new trading and clearing frameworks, in particular central counterparties, magnified the liquidity crunch by ratcheting up margin calls at the height of the crisis

- The much-expanded NBFI sector amplified the crisis, in particular hedge funds and money market funds

Market participants tend to emphasise the first 2, with supervisors, particularly the Financial Stability Board (FSB), recently focusing on the role of hedge funds and calling for more supervision.

Trading Book Capital Rules

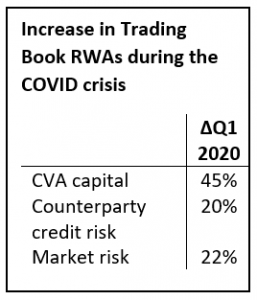

According to a survey of 20 banks by ISDA, GFMA and the IIF [1], trading book Risk Weighted Assets (RWAs) increased dramatically during the crisis (see figure 1).

The International Swaps and Derivatives Association, the Global Financial Markets Association and the Institute of International Finance

The International Swaps and Derivatives Association, the Global Financial Markets Association and the Institute of International Finance

In part this was caused by an increase in the number of Value at risk (VaR) back-testing exceptions. Under the current rules (known as Basel 2.5), banks are required to add a multiplier to their capital calculations if the estimated one-day risk under the VAR approach is lower than P&L more than 4 times a year. The size of the multiplier will increase as the number of exceptions increase.

It is true that supervisors moved to counteract this: for example, the European Central Bank announced on 16 April that the multipliers would be reduced temporarily. However, whilst this was welcome, by this stage market fears had already been subdued by the massive central bank intervention.

The new ‘FRTB’ [2] trading book capital rules are to be introduced as part of the finalisation of Basel III, and one of the aims is to reduce procyclicality. However, this is the most complex framework that have ever been introduced by Basel and has so many moving parts it is not clear that these rules will work as intended.

There are particular concerns about the P&L Attribution Tests which banks must meet to continue using the models approach to determining capital. Whilst the design of these new tests has improved from earlier versions, it is still likely that they could cause a huge cliff effect on capital requirements, in a similar way to the VaR backtesting rules. These tests are performed at a trading desk level to check that the P&L predicted by risk management models is consistent with accounting P&L models, with failure being defined as 4 or more breaches in any 12 month period. In stressed markets the failure rate of this test (and back-testing) is likely to increase, forcing many desks to move to using the standardised approaches. Before implementation it is crucial that the impact FRTB would have had in March 2020 is fully understood at a detailed level.

In any event implementation of FRTB has been delayed yet again in response to the crisis (by 1 year to 1 January 2023), and in the EU the plan is only to implement the regime as a reporting requirement, with capital requirements to be introduced sometime later. A notice of proposed rulemaking was apparently scheduled in the USA for Q1 2020 but has presumably been shelved in the wake of the market turmoil.

Market reforms: impact of central counterparties

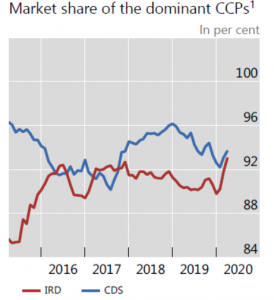

Arguably the most ambitious of the post GFC reforms was the fundamental overhaul of the structure of the derivative market itself. The core of these reforms was to require central clearing of standardised over-the counter (OTC) derivatives. This increased concentration risk by leading to a consolidation of both CCPs themselves and of the dealer/ clearing member community, as highlighted in a recent BIS study[1]:

- > 90% of interest rate (LCH) and credit derivatives (ICE) are cleared through a single CCP

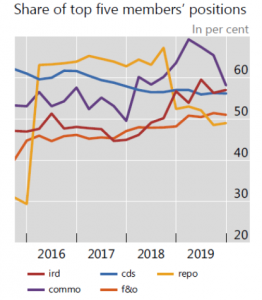

- >50% of interest rate and credit derivative positions at CCPs are held by the top 5 members.

This ’nexus’ between CCPs and big banks magnifies the potential risks: it seems ironic now that ‘too big to fail’ was advanced as a prime cause of the GFC!

CCPs collect both Initial and Variation margin to protect themselves against counterparty risk. Variation margin is used to settle losses incurred on a position and initial margin is an amount paid in advance to protect the CCP against non-payment of variation margin by a defaulter. Clearly if markets are very volatile, variation margin demands can increase dramatically , but it is the role of initial margin that is under scrutiny.

CCPs’ natural reaction in a crisis is to increase initial margin levels but this can be aggressively pro-cyclical, amplifying the liquidity drain in a stressed market. This clearly happened in Q1 2020: initial margin rates charged on some equity index futures contracts such as Eurostoxx 50 and the Nikkei 225 increased by >100%, and S&P500 and FTSE 100 by >90%, as identified in an important report by the FIA [4]. The margin calculation for OTC derivatives is more complex, so simple % changes are harder to estimate, but the more than tripling of CCP deposits with the Fed from $70 billion in mid-February to over $270 billion by mid-March supports the view that requirements increased hugely across the board (variation margin for a CCP is a zero-sum game: every dollar they collect from losers is paid to the winners).

The liquidity shock created by margin hikes are passed on quickly from banks to their customers: in particular other non-clearing banks, brokers, institutions, and investors, but also to the corporate world as well. Institutions will go the repo market to access liquidity in the first instance. However, this market has shrunk since the GFC, again in part due to regulatory reform (particularly the leverage ratio) making it less attractive for banks to provide liquidity in these markets.

The BIS and FIA articles identifies the problem but the solutions they propose are arguably not that radical: the rules CCPs operate under are supposed to prevent hiking margins in crises already but they don’t seem to work. It must be at least doubtful that further margin setting guidance will make a fundamental difference, although the detailed FIA proposals are sensible and might help to some extent. Given the amount of human as well as financial capital that has been invested in these reforms it may take a long time before there is an appetite for revisiting whether the dangers outweigh their benefits.

It is worth noting that the requirements for bilateral posting of initial margin for non-cleared derivatives was not fully implemented before the crisis (and has been delayed further as a result). If it had been, that could potentially have further intensified the liquidity stress.

Impact of the NBFI sector

In 2009, the G-20 mandated the FSB to co-ordinate implementation of the post GFC reforms. In an important recent report [5] the FSB acknowledged that a side effect of the reforms was to encourage the growth of non-bank financial intermediation (NBFI). Whilst the report acknowledges the impact of capital requirements and margin calls on liquidity, it also emphasises the role of strains in NBFI sectors in amplifying the stress, in particular:

- Outflows from open-ended investment funds and in particular money market funds

- The role played by ‘leveraged investors’ (especially hedge fund strategies to arbitrage the basis between cash Treasuries and their derivatives) in destabilising the US Treasury Bond market.

The industry has argued that the primary cause of the market turmoil was huge sales of treasuries by foreign investors and central banks, but the major regulators and supervisors around the world have echoed the concerns raised by the FSB, which has proposed a programme of work to strengthen the oversight of the NBFI sector. Co-ordinating global regulatory reform is challenging even within one sector such as banking as anyone who has followed the Basel project knows so this is clearly ambitious.

Summary

The post GFC reforms sought to strengthen the resilience of the banking sector and markets. Banks are clearly much better capitalised and more able to withstand stress than they were in 2007-8 but it is not clear that markets are more robust: the market reforms have introduced new complexities and stresses. Essentially, open credit risk has been transmuted into liquidity risk for most participants. This can accelerate and amplify stress at the institutional level and transmit it through the system more quickly. Perhaps we need to get used to more frequent crisis management and intervention by the authorities. Institutions and individuals need to prepare properly, stress testing their liquidity sources and needs. The old saw that ‘cash is king’ perhaps needs updating but the underlying sentiment may be more true than ever!

[1] The International Swaps and Derivatives Association, the Global Financial Markets Association and the Institute of International Finance

[2] Fundamental Review of the Trading Book: capital rules introduced through the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (Basel) co-ordinated through the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

[3] BIS Bulletin 13 :The CCP-Bank Nexus in the time of COVID-19 May 2020

[4] Futures Industry Association: Revisiting Procyclicality: the impact of the COVID Crisis on CCP Margin Requirements October 2020

[5] Holistic Review of the March Market Turmoil, November 2020